“The Great Polygamy Hotel”: Albert Robida (1848-1926) and the Popularization of Mormon Stereotypes in Nineteenth Century Fiction

by Massimo Introvigne

A paper presented

at the CESNUR 2010 conference in Torino.© Massimo Introvigne, 2010.

Please do not quote or reproduce without the consent of the author

Mormonism

in Popular Fiction

Mormonism

in Popular Fiction

In order to create distinctions between religions and “cults”, critics typically use stereotypes. These stereotypes concerning minority religions are reinforced by popular culture, including novels and later comic books, movies, and TV series.

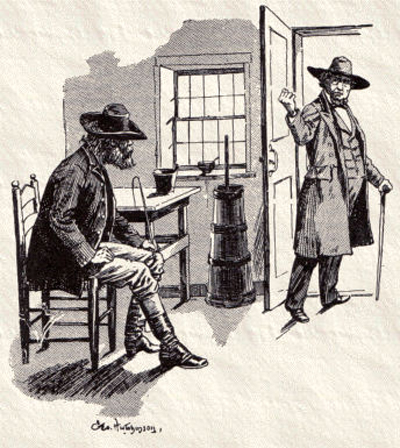

Some of the best known books concerning Mormonism have been written as “historical” fiction. American authors who have used to this method to write about Mormons include Artemus Ward (pseud. of Charles Farrar Browne, 1834-1867), Mark Twain (pseud. of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, 1835-1910), and Zane Grey (1872-1939). Considering the amount of material published about Mormonism in Europe, it is not surprising that a number of prominent European authors also showcased Utah and the Mormons in their fictional stories. Authors who had never visited Utah were more responsible for creating a certain image of Utah and the Mormons than those who actually wrote first hand travel accounts. As Larry McMurtry has observed, “lies about the West are more important (…) than truths, which is why the popularity of the pulpers — Louis L’Amour [pseudonym of Louis Dearborn LaMoore, 1908-1988] particularly — has never dimmed” (McMurtry, 1999, 55.) Long before L’Amour was born, Karl May (1842-1912), Balduin Mollhausen (1825-1905), Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), whose very first Sherlock Holmes story was about the Mormons (Doyle 1887; see fig. 1, depicting a threatening Brigham Young), Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), Emilio Salgari (1862-1911), Jules Verne (1828-1905), and Albert Robida (1848-1926) were immensely popular in Europe. Stevenson, Verne, May, and of course Doyle continue to enjoy widespread popularity not only in Europe but throughout Europe and even in the United States. Their books have been used by critics of the Mormon Church as if they were factually accurate.

Terryl Givens

has identified fifty-six novels which were written between 1850-1900

and included Mormonism in the plot. Mormonism was included because it

was “salacious, lucrative, pious, chivalrous, and patriotic all at

once” (Givens, 1997, 143.) More simply stated, Mormon polygamy was

illicit sex, and illicit sex has always been a seductive and tempting

subject. Most authors who used Mormonism as a subject — good and bad

— usually poked fun at its “peculiar institution,” polygamy.

Verne, Robida,

and the Mormons

Jules Verne,

the most popular French author of adventure fiction during the nineteenth

century, published his famous Around the World

in 80 Days in 1872. An English translation (The Tour of the World

in 80 Days) was published the following year (see fig. 2, Around

the World lampooned by Robida). In Verne’s book Phineas Fogg,

and his servant Passepartout travel through Utah on the Union Pacific

Railroad. During the journey a Mormon missionary named Elder William

Hitch boards the train and delivers a lecture on Mormonism. Passepartout

attends the lecture and remains even after most of the audience has

left the car because of the missionary’s aggressive sales pitch. From

Ogden, where the train “rested for six hours”, Fogg and his party

“had time to pay a visit to Salt Lake City, connected with Ogden by

a branch road”.

“The streets were almost deserted, except in the vicinity of the Temple, which they only reached after having traversed several quarters surrounded by palisades. There were many women, which was easily accounted for by the ‘peculiar institution’ of the Mormons; but it must not be supposed that all the Mormons are polygamists. They are free to marry or not, as they please; but it is worth noting that it is mainly the female citizens of Utah who are anxious to marry, as, according to the Mormon religion, maiden ladies are not admitted to the possession of its highest joys. These poor creatures seemed to be neither well off nor happy. Some — the more well-to-do, no doubt — wore short, open black silk dresses, under a hood or modest shawl; others were habited in Indian fashion.

Passepartout

could not behold without a certain fright these women, charged, in groups,

with conferring happiness on a single Mormon. His common-sense pitied,

above all, the husband. It seemed to him a terrible thing to have to

guide so many wives at once across the vicissitudes of life, and to

conduct them, as it were, in a body to the Mormon paradise, with the

prospect of seeing them in the company of the glorious Smith, who doubtless

was the chief ornament of that delightful place, to all eternity. He

felt decidedly repelled from such a vocation, and he imagined — perhaps

he was mistaken — that the fair ones of Salt Lake City cast rather

alarming glances on his person. Happily, his stay there was but brief” (Verne 1873, 216.)

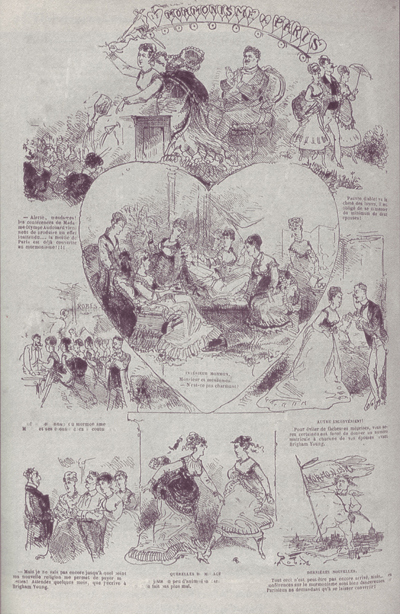

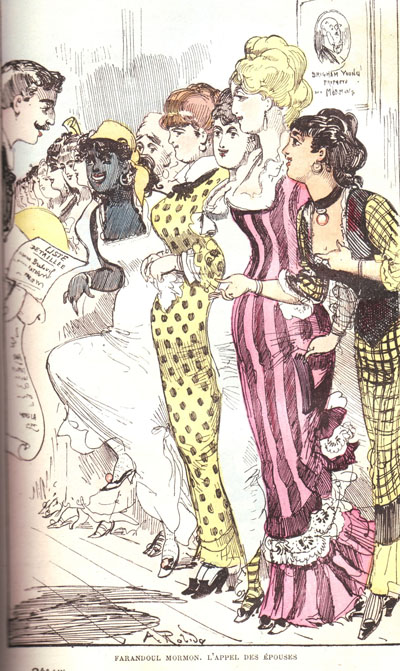

Verne’s Around the World became so famous that it generated a number of

parodies. Albert Robida, had achieved fame as a gifted illustrator before

turning 20 years old. In 1869, at age 19, he drew a series of cartoons

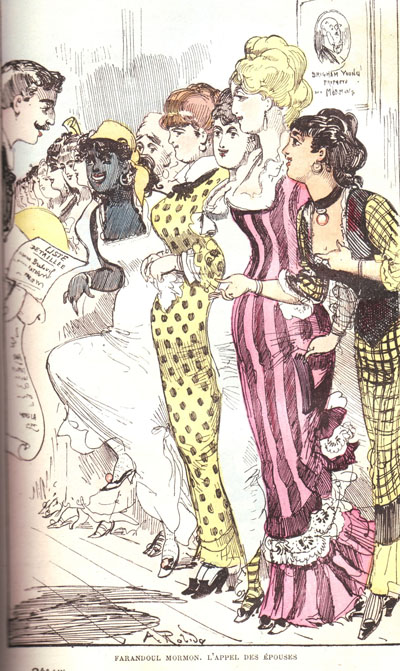

(very similar to a modern comic), entitled Le Mormonisme

à Paris (“Mormonism in Paris”: fig. 3), which were published

in Paris-Caprice on March 13, 1869 (Robida 1869.) Robida satirized

both Mormonism (with the usual mandatory references to polygamy) and

the prominent French feminist, Olympe Audouard (1830-1890), who visited

Utah in 1869 and wrote a surprisingly sympathetic description of polygamy.

Audouard’s lectures were, according to Robida, “beginning to have

an unexpected effect…half of Paris has already converted to Mormonism!!!!”

Saturnin

Farandoul meets the Mormons

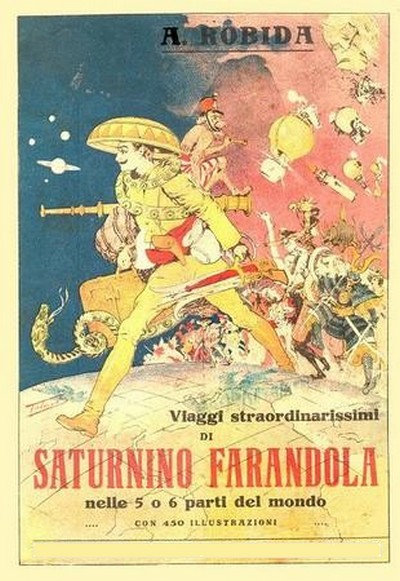

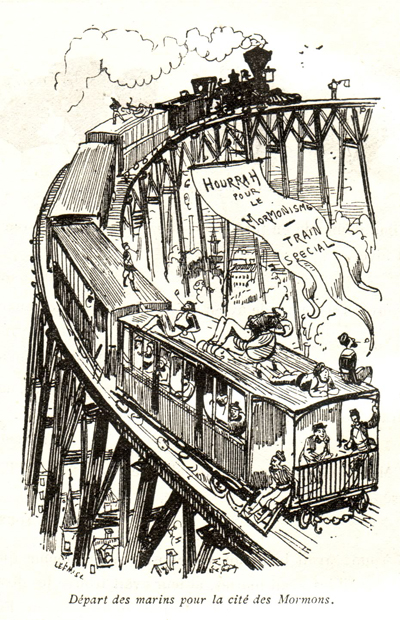

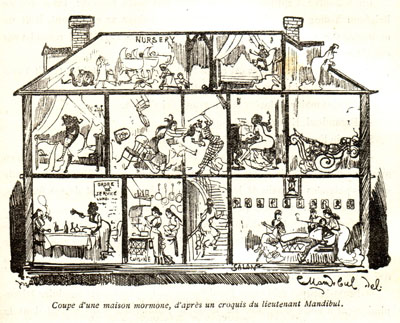

In 1879, Robida

published, in instalments, Voyages très extraordinaires de Saturnin

Farandoul dans les 5 ou 6 parties du monde et dans tous les pays connus

et même inconnus de M. Jules Verne (“Most Extraordinary Travels

of Saturnin Farandoul in the 5 or 6 Parts of the World and in all the

Countries Known and Even Unknown by Mr. Jules Verne”). While Verne’s

tour around the world blurred fact and fiction, causing some readers

to suspend disbelief, most of Robida’s tales — which included his

own illustrations — were parodies aimed at creating humor through

exaggeration rather than attempting to tell believable adventure stories.

Although Farandoul was never translated into English, it had

both authorized and pirate Spanish and Italian editions. In Italy, Robida’s Farandoul (fig. 4) was almost as popular as Verne’s Tour of

the World.

One of the

first Italian silent movies, was about Farandoul. Le avventure straordinarissime

di Saturnino Farandola, which was turned in Turin and released in

1913, was directed by Marcel Fabre (pseudonym of Marcel Fernández Peréz,

1885-1929), who also starred in the title role (see fig. 5). In 1938-39

the story was serialized in the Italian comic magazine Topolino (“Mickey Mouse”), which was republished several times. In 1977,

Italian television also produced a series on Farandoul (Saturnino

Farandola, by Raffaele Meloni) starring popular actor Mariano Rigillo.

In 1959 a spoof on the spoof was even published. That year a comic was

published which featured the character of “Paperino Girandola”,

or Donald Duck (“Paperino” in Italian) in the role of Farandoul.

It also went through several reprints. The very existence of this comic

book shows that Farandoul was a literary reference which was

immediately recognizable by most Italian children and teen-agers. This

was also confirmed in 1979 when another well-known author of Italian

comic books, Bonvi (Franco Bonvicini, 1941-1995), produced another spoof

of Farandoul, both as a comic and as a television cartoon, known

as “Marzolino Tarantola”. For whatever reason, as Farandoul gradually became less popular in France it became increasingly popular

in Italy. Today it is out of print in the country where it was originally

published.

Farandoul has a rich (and richly illustrated) section about Mormonism and Brigham

Young (1801-1877.) Farandoul, his second-in-command Mandibul, and the

mariners of their ship Belle Léocadie (including the Breton Tournesol),

“tired of the solitary life”, decide to convert to Mormonism and

embrace polygamy. Farandoul telegraphs Brigham Young announcing his

conversion:

“Brigham Young, delighted and flattered to have won for his religion such an important recruit, said he was placing himself at the entire disposal of Saturnin.

During the last few hours of the journey, the telegrams flew to and from:

“Found a splendid opportunity. Senator just divorced from spouses. Sixteen well-assorted women. Would throw in seventeenth into the bargain. Do you wish to avail yourself? Many applicants, but you would have preference.

Brigham Young

“Accepted. Thank you. Lieut. Mandibul wonders whether similar opportunity for him.

Farandoul

“Six negresses and a Chinese for the asking. Don’t speak French. Do we negotiate?

Brigham Young

“Mandibul additionally asks for half-dozen white women for the sweet chit-chat in the home”

Farandoul

“I’ve found them. Asked before closing whether Lieut. Mandibul is fair-haired.”

Brigham Young

“Blazing fair hair. Another request. Tournesol [Sunflower], thirty-three, volcanic temperament. Would like Mexican women?”

Farandoul

“Mandibul match made. A big lot of Mexican ladies for Tournesol. I shall be at the station.”

Brigham Young”

(Robida 1879, 171-72.)

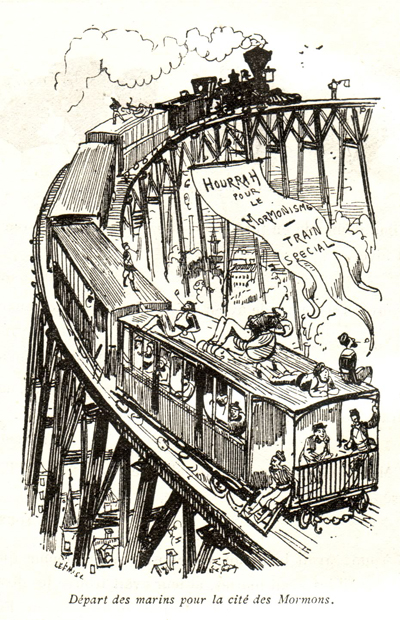

A wedding is

organized in Salt Lake City with due fanfare (fig. 6):

“At the station exit, the cortège went straight to the temple, where the registry documents had been prepared. All that was needed was a few rapid signatures and everyone repaired to the Great Polygamy Hotel, in the gala room of which, a magnificent banquet for three thousand had been provided by the municipality of Salt Lake City to the new converts. (fig. 7)

Brigham

Young, the bishops and the elders honored with their presence this gigantic

dinner, at which seas of Champagne were poured in honor of Farandoul.

We have no intention of reporting all the incidents, nor of enumerating

the toasts which were proposed to Mormonism, to the old and new faithful,

and to their amiable fractions, as Mandibul said, referring to his wives,

who were too numerous to be called his moieties or better halves”

(Robida 1879, 174-75).

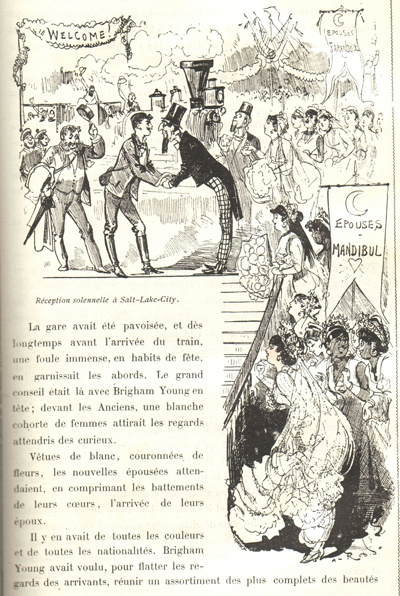

Farandoul,

having appreciated how Mormon homes work fig. 8), makes a great speech

in favor of Mormonism and polygamy, and is made a Mormon Bishop on the

spot (fig. 9). Unbeknownst to Farandoul, Brigham Young believes that

he could be a possible rival, and therefore plans the Frenchman’s

murder (an obvious allusion to the popular Danite theme) while Farandoul

is home expecting a pleasant evening in the company of his seventeen

wives.

“The ringing of the bell roused him from his ponderings; the seventeen ladies discreetly withdrew, leaving him alone with his visitor.

The latter had simply come to tell him that a meeting of the council of elders would be taking place that very evening, and Brigham Young asked the new bishop to honor the occasion with his presence, if the rigors of the journey allowed him to.

‘Lead on!’ said Farandoul.

And the indefatigable Saturnin, pausing only to offer a few words of explanation to the ladies, followed in the departing footsteps of Brigham Young’s messenger (…).

Night had fallen. Our hero was walking down the dark avenue which led to the Great Mormon Temple.

Unsuspecting, he had not noticed some shadowy figures following him noiselessly, while other shadows hid behind each tree.

His thoughts returned to his seventeen wives, and the smiling future which beckoned to him. Not a single dark shadow on the horizon, not a cloud in his sky...

Suddenly, an owl-hoot sounded behind him, and a cascade of human beings bore down upon his shoulders before he realized what had happened, and despite a desperate struggle, his assailants had thrown him to the ground, then bound and gagged him.

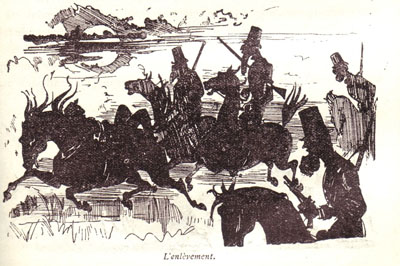

These men were masked! Even so, Farandoul thought he could make out among them two of Brigham Young’s followers whom he had glimpsed at the banquet. It was all plain to him!

Horses

were brought, and the bandits tied Farandoul tightly onto the liveliest

of the steeds and leapt into their saddles” (fig. 10) (Robida 1879,

180-81.)

Thereafter

Brigham Young orders Apache warriors to kidnap and kill Farandoul (an

allusion to the Mountain Meadows massacre), but the French traveler

pacifies them by painting designs on their skin. But he eventually falls

from grace because he spends too much time with their squaws, particularly

Rising Moon, the wife of Red Buffalo. He runs off with her into the

wilderness, while being pursued by Apache warriors. Farandoul must kill

two grizzlies to save their lives, and they wear their skins to disguise

themselves. After taking refuge from their pursuers in a cave full of

real grizzlies, the pair travel down the Colorado River, still pursued

by Apaches. They are dispatched over a waterfall by a ruse of the nimble-witted

Farandoul. He and his consort meet two trappers who first fire at them,

mistaking them for real grizzlies, then offered to take them to Santa

Fe, two days’ journey away.

Farandoul’s

first thought is to telegraph Mandibul at Salt Lake City. A reply soon

arrives. Mandibul and his companions, when they learn of the disappearance

of their chief, had abandoned their wives. In the meantime,

“Farandoul returned to the telegraph office; a message in the following terms was dispatched to Brigham Young: ‘You rascal, what have you done with my seventeen wives? Farandoul. Reply paid’.

Brigham Young replied with a telegram which betrayed his astuteness and hypocrisy.

‘Sir, After the incomprehensible flight which showed us that you were not a sincere Mormon, your spouses, blushing for shame at having ever, for one instant, been united to a man as bereft of convictions, are petitioning for divorce. An honorable Mormon, Matheus Bikelow, appointed Bishop in your stead, has afforded the shelter of his home to them. He has married them and will not abandon them!

Once again, Sir, your conduct has been unworthy, and I would suggest that you never show yourself again in the city of the Saints. Brigham Young”‘.

Since the

reply had been paid, Brigham, as we can see, had not been over-spare

with his words. Farandoul turned next to Bikelow, and asked for his

seventeen wives back” (Robida 1879, 207-08.)

Farandoul and

Bikelow agreed on setting the dispute through a duel and the Frenchman

suggested that “each adversary shall be mounted on a locomotive. Both

trains shall leave at the same time from New York and San Francisco,

to collide in the middle of the Central Pacific Railroad line” (Robida

1879, 208.)

Bikelow had

to accept Farandoul’s challenge. The latter’s crew had been vainly

searching for their captain, when in Nevada they came upon the news

of Farandoul’s duel with Bikelow. They join Farandoul as he prepares

to leave New York taking with him the special train with which he is

to confront Bikelow. The opponents are to meet at the Devil’s Bridge,

spanning the Nebraska river. The duel attracts considerable public attention,

and people gather in Nebraska waiting for the two trains, armed with

swivel-mounted cannon, to come together. As they meet, a murderous exchange

of fire damages Farandoul’s train, but Bikelow’s train causes the

bridge to collapse, and plunges over a hundred feet into the river.

The speed of Farandoul’s train causes it to reach the abutment in

time. “Now that honor is satisfied”, declares Farandoul, “I renounce

all seventeen ungrateful women; please telegraph the fact to Brigham

Young” (Robida 1879, 212-216.)

Mormons in Le Vingtième Siècle

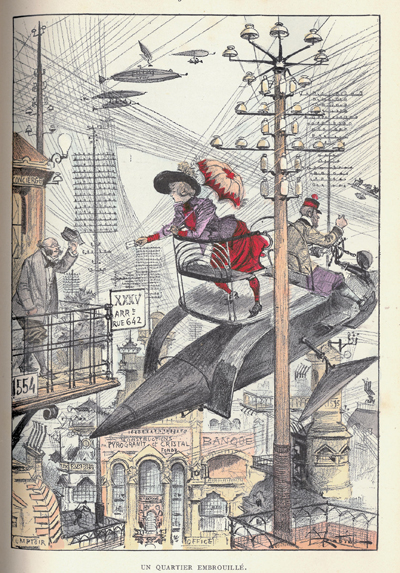

In 1882, Robida

began publishing installments of another novel entitled Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century). One year later these installments were collected and published in a

book. Although the book was less influential than Farandoul on

Latin European youth and in popular culture, it is now regarded as Robida’s

masterpiece, and remains in print in France. It has been translated

into English in 2004 in a critical edition by Wesleyan University Press.

It is a humorous science fiction novel, in which Robida anticipated

in astonishing detail some of the inventions of the twentieth century,

including telephones, airplanes (fig. 11), and television (fig.

12).. Mormonism is a side theme in the novel. The setting of the novel

is in France and England in 1953. Robida explains that in 1910, the

United States had become three nations: a Chinese republic in the West,

with its capital at New-Nanking (San Francisco), a German empire in

the East with its capital at New-Berlin (formerly New York City), and

a Mormon republic (formerly “the old states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona,

etc.,”), headquartered at Salt Lake City.

The Mormons,

sensing that their country would become the inevitable battlefield and

plunder of the two larger American nations, turned their attention to

their mother country of England, particularly when the British government

fled to India. In a matter of ten years, the Mormonization of England

was complete. “The land of the expression, “shocking!,” has become

the most shocking country on the planet. The House of Lords is

now the House of Bishops, and to be eligible for election to the House

of Commons, one must have at least eight wives” (Robida 1883, 316).

New landmarks include the Great Temple, modeled after that of Salt Lake

City, and, in Hyde Park, the Palace of the head of state (who is both

pope and president of the Mormon republics of Europe and America). Windsor

Castle is now a retirement estate “for widows of bishops and archbishops,

etc., etc.” (Robida 1883, 315)

Monsieur Ponto,

a Paris financier, has unwisely sent his son Philippe to England, now

the most dangerous country in Europe, on a crucial banking matter. Philippe

has dropped out of sight, and his father’s concern is only heightened

when he finally receives a letter - something fairly rare in

this modern day of telephone calls:

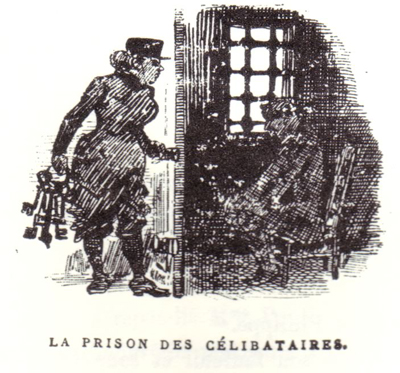

“Bachelor’s Prison, August 7, 1953

My dear father,

Such a funny country Mormonism has made of this New-England - how I would laugh if I were not in prison at the moment! Rest assured that I have murdered no one, nor committed the slightest misdemeanor. I am simply locked up in Bachelor’s-Prison as a matrimonial insubordinate. Don’t laugh, this is very serious! . . .

After coming out of the Calais tunnel, I found the aerocab of our London correspondent, Mr. Percival Douglas, as planned, and this gentleman looked after me himself. Just as we were leaving for the bank, I noticed a crowd on the docks in front of two enormous transatlantic dirigibles swarming with people. People were running, jostling to get close to these.

“So what is that?” I asked Percival Douglas.

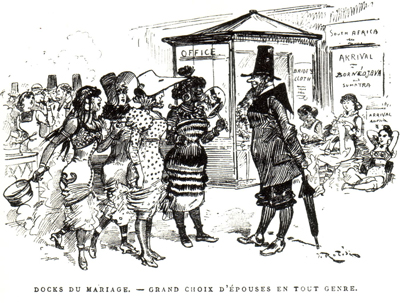

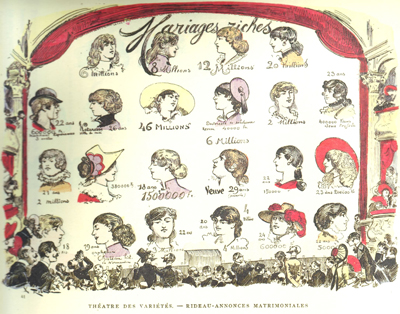

“It is an arrival of wives,” he replied coolly. (fig. 13 – some will be late auctioned: fig. 14).

I began to laugh, naturally, and asked to see the arrival a little more closely. Our aerocab parked ten meters above the docks. On the decks of the dirigibles I saw hundreds of young ladies and women of all colors and conditions, some well dressed and covered with jewels, draped in superb clothing - others poorly clothed.

“What is this?” I said: “yellow women, white or swarthy, even Negresses . . .”

“It is the overflow of the Indies, of America and Australia,” replied Percival; “there, they only marry one wife. Many young women therefore remain unprovided for; the agencies which we have in the five parts of the world enroll them for the promised land of the New-England . . .”

“Then all the ladies of this arrival will find spouses?”

“They will be conducted to the Marriage Docks, where they will remain until they receive a proposal.”

I broke into laughter. Since the institutions of the New-England are not widely known, I was ignorant of such useful docks! . . . they look like a massive Eastern inn. Four groups of buildings, eight stories of rooms, kitchens and work rooms where the young women demonstrate their abilities to visitors, drawing rooms, a garden where all are admitted. Superb! The structure is surmounted by a lighthouse . . . the Marriage Beacon. Its emblematic fires shine over the entire city of London, reminding those who are interested that they can come to the docks to light other flames. A civil officer of the state, established in the lighthouse itself, keeps his registers open all hours of the day and night.

. . . .

.The first person I saw the next day was a preacher who came to talk

to me about the beauties of Mormonism. As he left, he gave me an assortment

of Bibles and pamphlets: Mormon Virtue, by Rev. J.-F. Hobson; Shame on the Bachelor, Pity the Monogamous, sermon preached at the

great temple by Mr. Clakwell, vendor of imitation Champagne wines, and

archbishop; The Art of Managing Women, treatise by Mr. Fred.

Twic, Mormon archbishop, etc., etc.” (Robida 1883, 312-14.)

Young Ponto is quite surprised:

“This strange country! The men drink, smoke or sing hymns in the taverns while the women stay at home and work. Only the poor devils who have but one or two wives need labor. For the others - the lucky gallants fortunate enough to bring seven or eight “misses” before the civil officer - life passes tranquil and happy. I made it into several patriarchs’ homes, and saw that the motto was order and discipline! The husband is head; he is venerated and pampered. Besides, in each district and ward there is a sort of guard-room or house of correction for wives who might be contrary or rebellious. One word from a husband to the superintendent of police, and the policewomen come to find the guilty wife and take her to the Correctional House, where solitude and the sermons of preachers assigned to the institution induce salutary reflection.

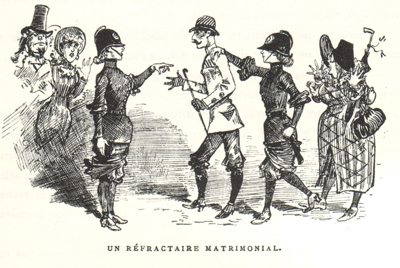

. . . . .Last Sunday morning, as I was descending from the aerocab to the pavement of Regent Street (with the idea of taking a walk before lunch), I noticed that passers-by looked at me strangely. Fathers threw me irritated looks, and when ladies saw me, their gestures showed I was an object of horror to them. I racked my brains in vain to figure out the reason for these repulsive manifestations when suddenly, two policewomen (fig. 15), sent by an old woman, came and seized me by the arms.

“Are you married?” they asked me.

“No!” I replied, surprised.

“No spouse?”

“None at all!”

“Oh!!!”

And they grabbed me resolutely by the collar. I offered no resistance. We thus arrived at the coroner’s. This magistrate began by putting the same question to me: “Are you married? — No, Sir, not yet! — Then, you are a bachelor? — Apparently! — This is serious! very serious!”

The coroner murmured, regarding me with a disapproving air. “I shall be obliged to send you to bachelors’ prison.”

— “But I am a foreigner!”

— “Everyone we arrest says that!”

— “But listen to me, you can tell very well from my accent that I am French!”

— “Everyone speaks French, more or less – that doesn’t prove anything. Do you have papers?”

— “You know very well there haven’t been passports since the Middle Ages.”

— “Then too bad for you, I’m sending you to Bachelor’s Prison. Enter your protests as you are able.”

The episode seemed so funny that I let them take me to Bachelor’s Prison, curious to experience this Bastille of unfortunate celibates.

But, oh! the walls, ten meters high, the barred windows, the massive doors: this is a serious prison (fig. 16). The turnkey-esse (for at Bachelor’s Prison the turnkeys are turnkey-esses) listed me coldly on the register and had me taken to a cell furnished with a bed, a table and a chair. Another jailor-esse brought me a bundle of old ropes and uttered a single word: “Work!” I asked for an explanation. I am condemned to eight days of forced labor: if I want to eat lunch and dinner, I must unwind the hemp of these old ropes, without cease, from six o’clock in the morning until six o’clock in the evening. At six o’clock I eat, and at seven o’clock I go to chapel where I hear Mormon sermons until midnight.

This sort

of existence hardly seems entertaining, and I dream of getting out”

(Robida 1883, 315-18.)

In the end,

it turns out that Percival Douglas is letting poor Philippe rot in Bachelor’s

Prison until he might agree to marry the Douglas daughters. Philippe

is saved in the nick of time by a good-looking young girl who is his

father’s secretary, sent to London and appearing at the prison, pretending

to be Philippe’s wife.

Mormonism,

Stereotypes, and Popular Culture

Popular fiction,

whose immediate theme is entertainment, plays an important role in sustaining

stereotypes about religions and other minorities perceived as “other”,

“bizarre”, or “fringe”. It may also sustain ethno-definitions

which exclude certain groups perceived as bizarre or ridiculous from

the sphere of “real” religion. Ethno-definitions, defined by Arthur

Greil as “the working definitions that social actors themselves use

in an attempt to make judgements in everyday life” (Greil 1996: 48),

are produced and negotiated in the course of social interaction. Greil

has observed that “when focus is on ethno-definitions, ‘religion’

is examined not as a characteristic which inheres in certain phenomena,

but as a cultural resource over which competing interest groups may

vie. From this perspective, religion is not an entity but a claim made by certain groups and — in some cases — contested by others

to the right to the privileges associated in a given society with the

religious label” (Greil 1996: 48).

Works by Robida,

popular as they were, were part and parcel of the 19th century

social construction of the stereotypical anti-Mormon cliché which defined

Mormonism as something less — and less serious — than a religion.

Jules Verne’s references to Mormonism were probably too quick to be

really influential; Verne, however, influenced both Robida and other

authors. The polygamy stereotype is still used today in any anti-Mormon

enterprise (fig. 17: gay activists protesting Mormon opposition to same-sex

marriage).

This is not

to suggest that Robida had an agenda in terms of perpetuating stereotypes

and sponsoring discrimination. Robida is mostly interested in satirizing

Jules Verne, and in creating humorous situations, which are easily realized

when dealing with polygamy Successful popular culture is neither ideology

nor propaganda, but may include elements of both. Propaganda disguised

as entertainment fiction is rarely successful. Good fiction, on the

other hand, may pick up elements of propaganda from external sources,

and more or less advertently disseminate them to much larger audiences.

Readers who would never be directly interested in religious propaganda

may be exposed to it as filtered and re-interpreted by the authors of

entertainment fiction. The latter genre, thus, plays an important if

neglected role in propagating stereotypes about minority religions,

and certainly deserves further study.

References

Doyle, Arthur

Conan 1887. “A Study in Scarlet.” Beeton’s Christmas Annual.

London: Ward, Lock and Co, 1-95.

Givens, Terryl L. 1997. The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths and the Construction of Heresy. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greil, Arthur L., 1996. “Sacred Claims: The 'Cult Controversy' as a Struggle over the Right to the Religious Label.” In David G. Bromley - Lewis Carter (eds.), The Issue of Authenticity in the Study of Religion, Greenwich (Connecticut) and London: JAI Press, 1996, 47-63.

McMurtry, Larry.

1999. Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, Reflections at Sixty and

Beyond. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Robida, Albert,

1869. “Le Mormonisme à Paris”. Paris-Caprice. n. 68, March

13, 1869.

Robida, Albert.

1879. Voyages très extraordinaires de Saturnin Farandoul dans les

5 ou 6 parties du monde ed dans tous les pays connus et même inconnus

de M. Jules Verne. Paris: M. Dreyfous.

Robida, Albert.

1883. Le Vingtième Siècle. Paris: G. Decaux. English trans.: The Twentieth Century, translation, introduction and critical materials

by Philippe Willems, edited by Arthur B. Evans. Middletown (Connecticut):

Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

Verne, Jules.

1872. Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours. Paris: Hertzel.

Verne, Jules.

1873. The Tour of the World in 80 Days. Boston: James R. Oswood

& Co.

Note

The collaboration of Michael W. Homer in preparing this paper is gratefully acknowledged.

Images

Fig.1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17