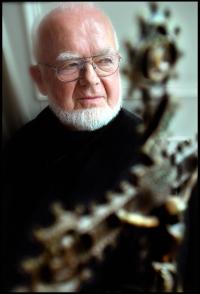

In memoriam: Johannes Aagaard (1928-2007)

by Massimo Introvigne

Dr. Johannes Aagaard, the father of modern counter-cult movement, passed away on March 23, 2007. Although Aagaard was mostly known to the general public as a counter-cultist, for the Danish and international Lutheran theological community he was above all a senior missiologist, who was called the originator of modern missiology in Denmark. From the late 1950s he made the University of Aarhus a well-respected international center in the field of missiology, sustained by his travels, knowledge of Eastern religions, and genuine passion for evangelization.

Dr. Johannes Aagaard, the father of modern counter-cult movement, passed away on March 23, 2007. Although Aagaard was mostly known to the general public as a counter-cultist, for the Danish and international Lutheran theological community he was above all a senior missiologist, who was called the originator of modern missiology in Denmark. From the late 1950s he made the University of Aarhus a well-respected international center in the field of missiology, sustained by his travels, knowledge of Eastern religions, and genuine passion for evangelization.

By travelling East, Aagaard met many young people who had converted to one or another Eastern new religious movement, and started orienting his various organizations towards an Evangelical approach to the criticism of “cults”. I met Aagaard in the late 1980s. We crossed swords on the issue of religious liberty and “cults”, but that did not prevent us from starting a respectful relationship, and I enjoyed several delicious Danish meals in his Aarhus home.

Most of our conversations revolved on the crucial difference between secular “anti-cult” and religious “counter-cult” movements, and the danger Evangelical Christians may encounter in co-operating with secular humanists, whose criticism of “cults” barely disguised their hostility against religion in general, or at least with those forms of religion which require a strong commitment, and are persuaded both of their social and political relevance, and that on certain issues the Christian position should not be negotiable. Well before Benedict XVI made the expression “non-negotiable issues” a trademark of his pontificate, I and Aagaard, while strongly dissenting on “cults”, did agree on this and shared a similar conservative view of Christianity. Although others have claimed to have “invented” the labels “counter-cult” and “anti-cult” as different between each other, in fact they were born from J. Gordon Melton's comments on the Evangelical counter-cult movement published in the 1986 edition of the Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America, and were further elaborated during lengthy conversations between the undersigned and Johannes Aagaard. In 1993, Aagaard asked me the put the distinction in writing for his Lutheran and Evangelical audience, which I did. To my knowledge, the first text discussing in detail the difference between anti-cultism and counter-cultism was my “Strange Bedfellows or Future Enemies?”, published in Aagaard’s Update & Dialog, no. 3, October 1993, pp.13-22. Besides consistently defending the decision of publishing a paper written by somebody like me obviously belonging to “the other side” in the ongoing “cult wars” of the 1990s, and disturbing to many, Aagaard effectively worked to limit the co-operation of Evangelical counter-cultists with those secular anti-cultists considered by him as engaged in promoting secular humanism, non-Christian positions on the “non-negotiable issues” about life and family, and criticism of religion in general. This attitude earned him several enemies, in France and elsewhere. On the other hand, he did attend several CESNUR events and in turn invited us to speak at his events in Aarhus and elsewhere.

Attempts to make his Dialogue Center international granted to Aagaard in later years recognition and success, but also internal problems in Denmark, and co-operation with much more extreme characters such as Thomas Gandow in Germany and Alexander Dvorkin in Russia. To his credit, and unlike those extremist counter-cultists, Aagaard always kept alive a conversation with scholars of the “other” side, such as Eileen Barker and myself, and never engaged in name-calling or defamation. Many, however, including myself, were critical of his consorting with characters such as Gandow and Dvorkin, and of his criticism of certain new religious movements which, in his later years, became increasingly bitter.

Unlike some of his fellow travellers, however, Aagaard never lost his unique Danish sense of humour. This made him a congenial dinner companion, and time spent debating with him was never wasted. While disagreeing with almost all of the conclusions he reached on “cults” and new religious movements, we at CESNUR prefer to remember him as a fine theologian, missiologist, and organizer. And we thank him for that tasty Danish bread.