Opus Dei and the Anti-cult Movement

by Massimo Introvigne (1994)

A translation of an article which appeared in Cristianità, no. 229 (May 1994, pages 3-12). The publication of this text is intended as a contribution to the history of the debate between academic scholars of religious movements and anti-cultists. The translation does not include any update. Obviously the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá is now Saint Josemaría Escrivá, John Paul II is the former rather than the present Pope and many additional pieces, unpublished and partially unknown in 1994, have been added to the debate on brainwashing.

A translation of an article which appeared in Cristianità, no. 229 (May 1994, pages 3-12). The publication of this text is intended as a contribution to the history of the debate between academic scholars of religious movements and anti-cultists. The translation does not include any update. Obviously the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá is now Saint Josemaría Escrivá, John Paul II is the former rather than the present Pope and many additional pieces, unpublished and partially unknown in 1994, have been added to the debate on brainwashing.

1. "Opus Dei. An Enquiry"

According to a recent study, among the first four books on some religious theme that the Italian public remembers having read, three of them are by Vittorio Messori [1]. This is in itself good reason to consider the appearance of any new work of this author and journalist —now well-known as the Pope's interviewer in the best seller Crossing the Threshold of Hope— as an authentic cultural event. Vittorio Messori was born in Sassuolo, in the province of Modena, Italy, in 1941. As he happens to have written on such a relevant topic in the life of the Church as Opus Dei —which has been the subject of many false accusations— the reasons for paying special attention to it are further increased. This latest book of Vittorio Messori, Opus Dei. Un'indagine [2] is presented as a report on a subject which, when he started his enquiry, the author was not particularly familiar with [3]. A press file on Opus Dei showed Vittorio Messori that this institution had aroused —with few exceptions— widespread hostility and rejection, and that around "the Work" (as many call it) an authentic black legend had been created [4]. The criticism levelled at it ranged from the incredible to the grotesque, culminating, especially after 1984-1985, with the accusation of being a cult [5]. Vittorio Messori has had the courtesy of quoting a number of my writings, and discussions I have held with him, in his research on the campaign against Opus Dei carried out by the anti-cult movement. I shall deal with this in the second and third part of this article, where I shall add new data and a few comments. Realising the very limited value of the press cuttings, Messori begins his enquiry by going to visit several institutions which are linked in some way with Opus Dei, starting with the ones related with universities [6]. He then studies the figure of the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá (1902-1975), the Founder of Opus Dei, and what he experienced on the 2nd of October of 1928. The author is quite right in his comment that this would be very difficult to understand unless it is taken in its religious, or rather, mystical dimension [7]. The Blessed Josemaría Escrivá always maintained that, properly speaking, he had not "founded" anything, he had only "seen" a project God had asked him to carry out. On the other hand, the Founder of Opus Dei, both by character and inclination, was not particularly interested in celestial visions, messages, or apparitions. His specific charism was rather more inclined towards the ordinary, towards the "peculiarity of not being peculiar" [8]. But this does not mean, as Messori says, that Opus Dei can be understood on the basis of purely sociological premises. And this is a very important observation to be borne in mind when examining any religious phenomenon, whether it is Catholic or not. In Messori's own words: "(...) what many intelligent people seem to have forgotten for decades is the obvious and blatant need to analyse a religious experience according to a religious framework" [9].

As a "religious reality" [10], Opus Dei presents at its centre a spirituality of work. The way proposed by the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá —but certainly not as if it were an exclusive or exclusivist way with regard to others that the Church accepts or proposes— consists in "sanctifying oneself with the perfect fulfilment of one's work". It is not a question of conceiving the quest for holiness and doing apostolate as a task to which one mainly dedicates the time left over from the normal commitments of one's job or work. It is, rather, the contrary —to do one's job as a way of sanctifying it, fulfilling each task with special care, "making an effort to be better always and everywhere" so that one's "professional prestige" may become, according to an expression of the Founder of Opus Dei, "a platform from which others are taught how to sanctify their work and how to adapt their lives to the demands of a Christian life" [11]. Carrying out this project of spirituality of work is not only entrusted to the personal initiative of each individual. It is supported by the whole structure of Opus Dei, which Vittorio Messori calls a "spiritual services agency", or a "service station for souls" [12]. Contrary to what a widespread myth would have us believe, this "spiritual agency" [13] is open to those involved in every type of work, not only to those who follow a liberal profession, or are business executives or academics, even though these may be more numerous in Opus Dei than in other Catholic institutions [14]. There is also a widespread misconception, in particular, about the structure of Opus Dei itself, whose present status has been approved by the Church after a complex juridical itinerary. Opus Dei is neither a movement or a religious congregation. In 1982 it became the first —and so far the only— personal prelature of the Catholic Church. A personal prelature is a sort of diocese without territory, to which members are subject as far as their spiritual life is concerned, while remaining in all other aspects under the jurisdiction of the diocesan bishop. Joining Opus Dei —which is the result of following a specific "vocation" within the Church— is done by a contract carried out by each one of the faithful with the Prelature. It must not be confused with religious vows [15]. The great majority of Opus Dei faithful are lay men and women who dedicate themselves to their ordinary family and professional tasks. Some choose to be celibate so that they can more freely dedicate themselves to the apostolates of the Prelature. These are called "numeraries". But others, who are generally married, are called "supernumeraries". A third possibility is that of the "associates" who choose to be celibate, but live with their own family and, for whatever reason, have less time available to carry out works of apostolate, in comparison with the numeraries. There are also external "cooperators", who can even be non-Catholic [16]. In Opus Dei there are also priests, incardinated in the Prelature, while a Priestly Society of the Holy Cross includes these priests of the Prelature as well as those members of the diocesan clergy who wish to follow the spirituality of the Prelature and receive its spiritual guidance, yet remaining subject to their own bishop for everything else [17].

To sanctify one's work, be it civil or ecclesiastic, demands, according to the spirituality of Opus Dei, a rhythm and regularity of life which is marked out by a set of pious practices. Vittorio Messori includes the use of the cilice (frequently mentioned as a proof of its alleged "cult-like" character), the Rosary, devotion to Our Lady and to the Guardian Angels [18]. As against the allegations of the "black legend" on Opus Dei, Vittorio Messori stresses the great variety of economic and political options found among its members. He point out that Opus Dei does not act 'en bloc'. This has been demonstrated recently in Italian politics where on a number of occasions Opus Dei members adopted different positions, without the least interference from the Prelature. One therefore has to be rather cautious in accepting media reports on political and economical matters which affirm that "Opus Dei has said..." or "Opus Dei has done...". Normally they just refer to personal options of individual supernumeraries or numeraries, who are acting in temporal matters with the freedom for which the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá had a real and especial devotion. This freedom means that it is not only possible, but a very normal and ordinary occurrence, that in the same country and dealing with the same social or political affairs, different members of Opus Dei should support different solutions [19].

An example of freedom of choice in secular matters with which Messori ends his enquiry is the attitude of members of Opus Dei adopted with regard to General Francisco Franco's government in Spain between 1939 and 1975 [20]. This is supplemented in an annex —"C'era una volta Franco" [21]— written by the historian Giuseppe Romano, a numerary member of Opus Dei. Vittorio Messori first points out that the Catholic social teaching "(...) has not 'absolutised' any political form, as we today (having shaken off the 'red' threat and the 'communitarian' intoxication) run the risk of doing with a democratic-liberal-capitalist system". To collaborate with a non-democratic government such as that of General Franco, therefore, "(...) was not 'shameful' or some sort of 'crime'". It was a government "(...) that was totally legitimate and recognised by the international community" [22]. Furthermore, the Spanish State in the times of General Franco was "(...) for at least 25 years publicly praised by the bishops of that country. There was, therefore, nothing to forbid a Catholic to collaborate with it" [23]. Having laid down the above premises, the alleged "collaboration" between Opus Dei and the Franco regime can now be clarified. If it is true that several Opus Dei members, exercising their own free rights, were ministers in some of the governments formed by Franco during the last days of his regime, it is not less true that other members of Opus Dei took part in political organisations of a different kind, and wrote in newspapers in opposition to the Franco regime. To give an example, the members of Opus Dei held very different opinions on what type of Monarchy should hold sway at Franco's death. Finally, Vittorio Messori points out that it is interesting to notice how all the detractors of Opus Dei discuss all these events, knowing perfectly well who among Franco's ministers and collaborators belonged to Opus Dei and who did not. This would prove that the "black legend" about Opus Dei being a "secret society" is a myth that should be reassessed. Certainly, as it is not a religious order, Opus Dei has no distinct sign or habit by which each one of its nearly eighty thousand members can be immediately identified. But, in sharp contradiction to what the widespread myth proclaims, its statutes are public (and indeed have been published, and are easily obtainable in book shops). "All those who know and deal with Opus Dei members", says Messori, "know perfectly well if they belong to the Work, for although they do not boast about it, neither do they hide it" [24].

2. The Campaign of the Anti-cult Movement against Opus Dei

A. Its origins.

In the third chapter of his book, Vittorio Messori mentions the attacks of the anti-cult movement against Opus Dei, and uses paragraphs from some of my publications —especially from Le Nuove Religioni [25]— to give a general explanation of the anti-cult movement and how it differs from what has been called the counter-cult movement. I do not intend to repeat here what Messori has already dealt with brilliantly, and I have studied in an article also published in Cristianità [26]. I shall simply remind the reader that the counter-cult movement, arose from a religious background, of a mainly Protestant evangelical character, in the United States of America. It criticises "cults" from a qualitative point of view, showing up the doctrinal aspects that are against Christian orthodoxy.

On the contrary, the anti-cult movement arose from a secularist background and it claims that it is exclusively concerned with deeds and not with creeds. It will denounce as "sectarian" any form of religious experience which, from a quantitative point of view, appears to be more intense than modern secularism is ready to tolerate.

Although its promoters are not particularly friendly towards Catholicism, the evangelical counter-cult movement has rarely concerned itself with the internal reality of the Catholic Church, and it has in fact hardly ever attacked Opus Dei as a "cult". On the one hand, Opus Dei has, indeed, no "doctrine" of its own, different from the Catholic doctrine. On the other, the evangelical counter-cult movement is conscious of the fact that the alleged excesses of apostolic zeal that is at times attributed to Opus Dei could well be attributed to Protestant groups and movements, as can be seen from the attacks that have been levelled at some of them by the anti-cult movement. Vittorio Messori's book gives me the opportunity to add a few further considerations.

The anti-cult movement and aversion against Opus Dei began in completely autonomous and separate ways.

· The campaigns against Opus Dei, as Messori himself point out, which were promoted from outside, and also unfortunately from within, the Catholic Church, are nearly as old as the entity founded by the Blessed Josemaría Escrivá.

· They were particularly intense during the 1960's and, in England, in the years 1980-1981. This last campaign ended in 1981 when Cardinal Basil Hume, Archbishop of Westminster, published some "recommendations for the future activity of members of Opus Dei within the Westminster Diocese", published with the intention of ending the polemics which were harmful for the whole Church. This was, however, made use of by the opponents of Opus Dei who made them out to be a confirmation of their own criticism [27].

· The earliest attacks against Opus Dei arose from within the Catholic Church, especially among members of religious congregations, who did not look kindly on Blessed Josemaría Escrivá's ideas of setting up a different entity which would be a tertium genus between religious orders and associations of the faithful.

· Later, these attacks took on a more doctrinal or political character. All types of Catholic "progressive" groups labelled Opus Dei as "conservative" and averse to any type of "aggiornamento" in theology and, in particular, to any form of "liberation theology" which would show direct Marxist influence.

In the meantime, Opus Dei continued to grow, reaching the present figure of nearly 80,000 members. That growth, not only in number of members but also in apostolic activities, could not but provoke the secularist world, that had got accustomed to receiving with satisfaction successive statistics on the Catholic Church, which apparently showed an unstoppable decrease in the number of faithful, of apostolic activities, and of associations as well as in the number of members of religious orders.

For qualitative and quantitative reasons, Opus Dei thus found itself in the midst of two ecclesiastical battle fronts. First, it was in the line of fire between "progressive" Catholics, who were for ever invoking, generally inopportunely, a "spirit" of the Second Vatican Council which went against the letter, if the matter so required, and the Catholics who were faithful to the doctrine of the Church as taught by its Magisterium.

Secondly, Opus Dei was at the forefront of the battle between anti-Catholic secularism and a Church which was increasingly less ready to accept the future role of cultural and social irrelevance that the prophets of the contemporary post-Enlightenment wanted her to play.

The secularist anti-cult movement, as Messori cleverly points out, arises from a similar reaction. Sectors of the secularist world could not tolerate any "return to religion" which would turn the tables on what they had confidently predicted that would happen: "There was no longer any room for religion", Messori says, "in a postmodern technological culture". Or, in other words, what the proliferation of "new religions" proved was that "what was happening was exactly the opposite", as always, "of what had been predicted by the usual 'experts': sociologists, futurologists, and even theologians and specialists in different religious matters, not excluding many priests and bishops" [28]. As it had been forecast that religion was set on a course of irreversible decline and the new interest of young people for religious phenomena could not happen spontaneously, the anti-cult movement concluded that something sinister and non-spontaneous must have happened. It then applied to the religious movements the theories of "brainwashing", that had been devised to explain the (relative) success of the communist North Korean and Chinese "re-education camps" during the Korean war. The enemies of the anti-cult movement (those groups that were accused of practising "brainwashing") were, in the 1960's and 1970's, rather removed from the world of Christian Churches and worldwide Christian communities. The culprits were mainly the Children of God (now evolved into The Family), together with those whom the anti-cult movement would soon begin to call "the big three" among their adversaries: the Unification Church of Reverend Sun Myung Moon, Scientology, and the Hare Krishna movement.

There then arose, as Messori points out, a new profession which offered the parents of those who had joined a new religious movement to be given a "brainwashing" in reverse. This "deprogramming" consisted in kidnapping the young person in question from the clutches of the movement, locking him up for some days or weeks in a motel room, or in a private house, and subjecting him to physical or psychological pressures until he renounced his adherence to the movement. The "deprogrammers" (whose activity seems to be in decline, but has not ceased altogether) were neither doctors or psychologists, but ex-members of those movements and, even more frequently, people who could only claim to have a notable physical strength, and before becoming deprogrammers had carried out various assignments which ranged from having acted as personal bodyguards to having been involved in thefts or in robbery [29]. The lucrative business of deprogramming, which brought in ten to twenty thousand pounds per treatment for the deprogrammers, required an ideological justification, as well as a political structure to support them. Thus, the anti-cult associations were formed around the first deprogrammers. They were strictly secularist, and have now been transformed, little by little to become the present CAN (Cult Awareness Network) and AFF (American Family Foundation), which have supported with helps of various types the setting up of similar organisations in different countries all over the world. Some psychiatrists (severely criticised by their own professional colleagues) devised a theory of "mental manipulation" which in fact applies the metaphor of "brainwashing" (although they prefer to avoid that controversial label) to the activities of new religious movements in order to justify their deprogramming. The activities of these psychiatrists suffered a severe setback when, in May 1987, the American Psychological Association, perhaps the professional association with the greatest authority in the world in the field of psychology and psychiatry, rejected after an extensive study a report applying the theory of mental manipulation and of brainwashing to religious movements as "not scientific" [30]. By changing their terminology and their names when needed, the activities of the anti-cult movements (and in a certain way also of the deprogrammers, although the best known had been arrested in different countries) have gone on until the present day. In the meantime, and in order to survive, the anti-cult movement and the deprogrammers have had to extend their theatre of operations, concerning themselves not only with the "big three", or with The Family, but with a wide range of religious (and sometimes not even religious) groups, which were conveniently labelled as "cults".

B. The Coming Together

It is in this context that the coming together of the anti-cult movement and the opponents of Opus Dei took place.

· It is necessary to keep in mind, as a starting point, the ideological framework of the anti-cult movement rising from a secularist attitude of not admitting any social phenomenon that would disprove its thesis that religion is bound to lose importance as time goes on, in the modern and postmodern world, and that there is no real need for it. Let it be also recalled that what is called "secular humanism" in the United States of America is nearly always associated (although there are exceptions) with militant liberal, "leftist", policies. These run counter to the conservative new evangelical, and fundamentalist, Protestantism and new religious movements, associate with conservative political causes, such as the Unification Church of Reverend Sun Myung Moon [31].

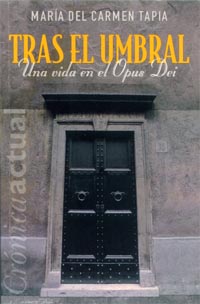

· And so, in 1984 and 1985, a political lobby of declared enemies of Opus Dei got in touch with anti-cult movements. During those years, one of the strongest attacks was being prepared against Opus Dei in Europe, from Catholic "progressive" circles, which crystallised in the publication of two books, one by the Paulist religious, Giancarlo Rocca [32], and the other by the Spanish sociologist, Alberto Moncada [33], an ex-member of Opus Dei, as Messori says. It was during those years that Penny Lernoux (1940-1989) was visiting Europe to collect material for a book on "Catholic cults". She was a North American journalist who had specialised in Latin American issues and had made a name for herself publishing a series of writings aggressively defending a Marxist inspired "liberation theology", fiercely attacking whoever was opposed to that theology [34]. Penny Lernoux acknowledges her repeated contacts with the "Vaticanologist" Giancarlo Zizola, with the already mentioned Giancarlo Rocca and Alberto Moncada, and, in the United States, with María del Carmen Tapia, an ex-member of Opus Dei who was a research worker at the University of California at Santa Barbara [35]. Apart from being actively engaged in spreading propaganda against Opus Dei, María del Carmen Tapia was also deeply involved in the heated arguments on "cults" that took place around that time between the specialists in religious sciences at the University of California. A small group of lecturers there, who were in favour of the activities of the anti-cult movement opposed other academics, and J. Gordon Melton in particular.

It was María del Carmen Tapia who put Penny Lernoux, and shortly afterwards Alberto Moncada in touch with CAN, the main anti-cult organisation of the USA [36].

· Towards the end of 1985, the Cultic Studies Journal, a CAN publication, brought out a first attack on Opus Dei, making use of the 1981 "recommendations" of Cardinal Basil Hume, the meaning of which, as I have already mentioned, has repeatedly been maliciously represented [37]. The book of Giancarlo Rocca was published in 1985, and that of Moncada in 1986. In that same year of 1986, questions were asked in the Italian Parliament as to whether Opus Dei was a "secret society" as a sequel to the Masonic Lodge, P 2, scandal. The polemics ceased when the then Minister of Home Affairs, Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, gave an official reply [38].

· In 1987 and 1988 the accusations against Opus Dei —that it was a "cult", that it used "brainwashing", and that, especially in Spain, its members required deprogramming treatment— spread from the United States, where CAN operates, to other countries where there were organisms associated with it or financed by the anti-cult movements in America. This took place notably in France, where the Association de Defense de la Famille et de l'Individu (ADFI) operates, and in Spain where several organisms are quite active, such as Pro Juventud and the Catalan Assesorament i Informació sobre Sectes (AIS).

· Towards the end of 1986 the first association for co-ordinating anti-cult groups, particularly interested in attacking Opus Dei, was formed in New York. It was called An Ad Hoc Alliance to Defend the Fourth Commandment, in reference to the alleged conflict between parents and their sons or daughters who were members of Opus Dei. It fixed its address in a Madison Avenue apartment in New York [39]. Another association sprung from that group, it took the name of Our Lady and St. Joseph in Search of the Lost Child, with John Garvey as director. At the meetings of CAN, ADFI and the other associated groups even some Catholic priests turned up to denounce Opus Dei as a "cult". For instance, the Dominican Kent Burtner, from San Francisco, and the Diocesain priest Fr. Jacques Trouslard, who had been Vicar General in the Diocese of Soissons and one of the most active members of the ADFI. In the United States, Fr James McGuire is known to have taken part in the activities of CAN. He is the director of the Newman Centre for Catholic students at the University of Pennsylvania. Fr James McGuire, is said to "share many other observers concern about alleged cultic aspects of Opus Dei". He was opposed to the "proselytisers" of Opus Dei and "other evangelical groups" at the University where he works [40]. When Fr Jacques Trouslard, in 1993, declared to the author of a vicious anti-cult publication produced by the ADFI that "he had started many years ago an investigation with families concerned about Opus Dei", against which he wished to prepare an authentic "requisition". Fr Jacques Trouslard declared that "it is not because Opus Dei is the preferred institution of the Holy Father, that I am willing to be silent" about a whole series of evident "cultic characteristics", among which could be counted: "indoctrination by means of intensive courses", "infiltration into the whole network of social life", "aggressive proselytising", "the usual cover found among all cults, such as camps, trips, shows, schools", and so on. As a genuine member of anti-cult groups, Fr Jacques Trouslard insisted that "he was not concerned about doctrines nor creeds", but only with behaviour, and that he was completely indifferent about the beatification of the Founder of Opus Dei. On the 14th of May, 1992, a few days before the beatification, Fr Jacques Trouslard declared to two newspapers and to two television networks that "this beatification is not my problem, even though it does imply an approval of Opus Dei. To amuse you, I am ready to say: Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer has been beatified, and I am laughing beatifically..." [41].

Before the beatification which took place on the 17th May 1992, the anti-cult movement and the opponents of Opus Dei had come together to carry out other common initiatives. In 1989 a book by Michael Walsh, a Catholic ex-religious, had been published, The Secret World of Opus Dei [42]. In spite of containing expressions at times of a rather cautious character, the book on its front cover proclaims that Opus Dei is "a cult" or "a sect" and concludes with the words that "it is not merely, as a sect, less than Catholic. It is less than Christian" [43]. Michael Walsh's book is so full of errors and shows such lack of precision that it makes one doubt it has been written in good faith [44]. Michael Walsh's background is significantly more interesting. As an ex-Jesuit, he was already hostile to Opus Dei —and, like many other critics of Opus Dei, a fanatical defender of the "theology of liberation"— even when he was a Catholic religious. Michael Walsh tried to enter into the world of specialists of new religious movements by collaborating with INFORM —Information Network Focus on Religious Movements— an authoritative organ based in the London School of Economics, and which, as it happens, does not have an anti-cult approach [45]. Fr Jacques Trouslard, the same as Michael Walsh, admits that his campaign against Opus Dei had started "as early as 1963", and it was only later that he had entered into the world of the anti-cult movements when he started his collaboration with the ADFI [46]. In 1989, the year she died, People of God, Penny Lernoux's magnum opus, on "Catholic cults" was published. The book is mainly concerned with attacking Opus Dei but, as the term "Catholic cult" would hardly be credible if it only applied to one reality, she also deals with Comunione e Liberazione and with TPF, the Brazilian Society for the Defence of Tradition, Family and Property, together with its sister organisations, as well as referring to Alleanza Cattolica. That reference to Alleanza Cattolica is sufficient to show what type of "scientific" method has been used by this American journalist in her writings. Penny Lernoux accuses Alleanza Cattolica of being just an Italian "front" for the Brazilian TFP, of carrying out an intensive indoctrination of minors without letting their parents know, and of believing that Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, the founder of the Brazilian TFP, is "immortal". One of the reference numbers of a note found at the end of the book, might give a casual reader the impression that these grotesque accusations are documented in some way. The note, in fact, just reads as follows: "Cristianità, April 1983; Alleanza Cattolica (Italy), November 1984 and February 1985" [47]. But in the number of Cristianità for April 1987 there is not the slightest mention of Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira —nor, needles to say, of his "immortality", or of methods of forming the young. Most of that issue is dedicated to covering a lecture given by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger on the subject of catechisms. As for a journal called "Alleanza Cattolica" —and its supposed issues which the note refers to, of November 1984 and February 1985— it simply has never existed. One can only conclude that the informants of Penny Lernoux on Alleanza Cattolica —and she quotes and thanks the staff of the Italian Catholic left-wing news agency called ADISTA [48]— have provided her on this as on other subjects information which, to say the least, is most inaccurate.

In spite of the very poor scientific quality of the books written by Michael Walsh and Penny Lernoux, the notion of "Catholic cult" made headway. Alberto Moncada presented it, in July 1990 at the XII World Congress on Sociology held in Madrid, with a lengthy report entitled "Sectas católicas: el Opus Dei". In the first page of his report, Alberto Moncada praised my work, Le sette cristiane [49]. In a later version of that text written by Alberto Moncada the praises he had addressed to my work were omitted, for reasons that go beyond the purely personal anecdote, and that I think are worth mentioning. At that time, the anti-cult movement had decided to launch a campaign against Opus Dei to prevent —if possible— the beatification of its founder in 1992, or at least to plant doubts and confusion in the public opinion on the occasion of such beatification. It would have been ideal to launch that campaign from a prestigious and neutral platform, which would not be the case, for instance, if it had been from one of the annual meetings of CAN, for it is neither academically nor scientifically properly qualified, nor for that matter, neutral. In 1991, the annual seminar of the CESNUR, the Centre of Studies on New Religions, was meeting at Buellton, in California. It had been organised in collaboration with the Institute for the Study of American Religion, based at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Considering what a central position California has in the world of new religious movements —and its objective journalistic importance— a large gathering of delegates from the Churches and representatives of the main religious denominations was foreseen, including many journalists. The number of people expected would be much greater than would normally attend the CESNUR seminars, which are only reserved for scholars, and which are not normally much publicised. The opportunity seemed a very favourable one, and pressures of different kind were brought to bear so that a paper by Alberto Moncada on Opus Dei as a "Catholic cult" would be accepted. The organisers agreed among themselves to refuse the proposal, explaining that the activities of CESNUR related exclusively to "new religious movements", and not to already existing entities operating within the Churches and major religions, which is what Opus Dei was. After they had informed Alberto Moncada —with due politeness— about their decision, they were greatly surprised to receive a reply from the Spanish sociologist, who even protested about the presence of a Catholic Bishop, Giuseppe Casale, in the final session (sitting beside a Lutheran pastor and a Methodist minister). "I lament", wrote Alberto Moncada in a letter dated 5 April 1991, "that you have taken this exclusivist decision, and I must honestly say that the structure of the seminar, with a Catholic bishop as a final speaker, sounds very much like an alliance with the Roman Church in its market squabble against other cults. It is an alliance that shows little respect for academic independence and the opinion of those of us who believe that in our ecclesiastical world, there are already sufficient cultic elements, above all under the pontificate of the present pope" [50]. This curious letter —in which the reference to "our ecclesiastical world" was in contrast with the mention of "the Roman Church" as a cult fighting "other cults"— was a prelude for other surprises. Among those invited to present their point of view to the academic specialists who were present at the seminar of Buellton, as tends to happen, although not always, in CESNUR-sponsored seminars there were representatives of some new religious movements and of anti-cult movements, CAN among others. Forming part of the delegation of CAN —whose cofounders, Priscilla Coates, I am bound to say presented her rather debatable ideas in a courteous and respectful attitude towards her hosts— that turned up at Buellton, was María del Carmen Tapia, whom I have already mentioned as an active anti-cult campaigner, specialised in attacking Opus Dei. Ms Tapia asked to read a declaration against Opus Dei which was completely out of character with the scientific nature of the seminar, and was strongly opposed, in particular, by myself. She then decided to cause an incident at all costs —for the benefit of the journalists who were present— trying to grab me by the lapels of my jacket. Unfortunately for her, the incident was not noticed: the public did not realise what was happening, and neither did the journalists notice in the incident anything worth reporting. For the record, the security guards of the hotel had kept a close watch on Ms Tapia because, dressed entirely in black, with a cross hanging from her neck, she had been mistaken for a devotee of one of the satanic groups that had for years been present in California.

Having failed in their attempt to use an academic platform to launch their anti-cult campaign against Opus Dei, Ms Tapia and her friends decided to follow a journalistic approach by contacting Newsweek —the USA magazine, which like its competitor, Time Magazine, had always lent a willing ear to the themes supported by the anti-cult movement. In the issue of 13 January 1992, under the title of A Questionable Saint, Newsweek relaunched the thesis of Opus Dei as a "Catholic sect" [51]. The article had been disclosed to the international press and made ample echo also in Italy [52]. The press campaign did not, of course, prevent the beatification, which was celebrated before a great gathering of people in Rome on the 17 May 1992. However, the attacks of the anti-cult movement continued, and once again the task of presenting Opus Dei as a "sect" had been cleverly entrusted to a Catholic religious, the Dominican Kent Burtner, at the 1992 CAN Congress. On that occasion, Fr Kent Burtner declared that, "(...) although Opus Dei maintains formal and nominal lines of accountability in the Church", it in fact "behaves very much like a garden-variety cult" [53].

In 1993 a new and significant event took place at an international conference on "Totalitarian Groups and Cultism" organised by several anti-cult movements from different countries, that took place in Barcelona on the 23 and 24 April, 1993. The preliminary programme, which had been prepared in 1992, listed among the lecturers a number of European representatives of the Catholic world alongside the best known United States leaders of the anti-cult movement. In December 1992, the Spanish sociologist, Alberto Moncada, figured among the speakers, and a preview of the report he proposed to read on Opus Dei as a Catholic cult was being circulated, which he would have presented practically in its entirety to the Barcelona congress. CESNUR denounced the foreseeable attack against Opus Dei masked by the organisers' invitation to qualified representatives of the Catholic world. As a result, some of the Catholic specialists who had announced their intention to take part in the Barcelona congress —and who figured in the provisional programme— announced their withdrawal [54]. As foreseen, Alberto Moncada at the Totalitarian Groups and Cultism Congress attacked Opus Dei violently, repeating his 1990 intervention, adding new injurious remarks. For instance: the behaviour of the University Lecturers of Opus Dei, who dedicate part of their time forming the younger members, was said by this Spanish sociologist to be —without any further justification— tantamount to "spiritual pederasty" [55]. Opus Dei was, again according to Alberto Moncada, a "cult" because it practises "indoctrination" an the manipulation of the personality of its adherents "to the point of schizophrenia". The "mental manipulation" is said to be carried out also through mass gatherings, in which "the Polish Pope exhibits his great powers as an actor" [56], and therefore to require —according to the typical mental schemes of the anti-cult movement— the intervention of the public authorities to forbid such "manipulations" and "indoctrination", with or without "Vatican approval". The anti-cult movements, according to Alberto Moncada, could make an important contribution "by informing, publicising, and warning the judicial powers and those responsible for the public order about the violation of human rights, which are the only ways open and the only defensive mechanism against the Opus Dei cultism, at least as long as this organisation enjoys the favour of the Vatican, and the Vatican continues to be directed by its present protagonists" [57]. This activity, according to Alberto Moncada, had fortunately already started with the foundation of what in Barcelona was presented as "Odan Network", defined as "an international network for informing about the activities of Opus Dei, with headquarters at Pittsfield, in Massachusetts" [58]. In fact the name of that organisation is simply ODAN, which stands for Opus Dei Awareness Network, which has close links with CAN, to which its very name makes an obvious reference [59]. As for the analysis he makes of Opus Dei, the Spanish sociologist's report is of such low intellectual level that it borders on the ridiculous. According to Alberto Moncada, for conservative Catholics "the intellectual options are being whittled away" and the enemies of "progress", who can easily be distinguished by their stand against abortion and against the "theology of liberation", will end up by becoming small enclaves which can only be defined as "cults". From this point of view, Alberto Moncada sees Opus Dei as "as doctrinally very similar to the movement of cardinal [sic] Lefevre [sic]" [60]. Unfortunately —and as a contradiction which undermines the validity of his analysis— Moncada admits that these "cultic" enclaves have acquired an unforeseen importance in the Catholic Church thanks to "cardinal Wojtyla [sic]", who "(...) has been helped effectively and faithfully by Opus Dei in his own special counter-reformation, against the spirit of the Second Vatican Council; the beatification has also represented an acknowledgement of this support". A recent fruit of this collaboration, Alberto Moncada goes on to say, "has been the Vatican Catechism, whose precepts on property and economics presume a return to the doctrines of XIX century popes, passing and trampling over encyclicals such as Populorum Progressio and endorsing the opinion that the so-called social teaching of the Church does not want to substitute capitalism but to baptise it". As these ideas cannot evidently be sustained at the end of the XX century, one could only convince some people by "cheating them", or even better by indoctrinating them when they are still "a small boy or girl", without "giving them time to consider other alternatives (...)". And thus one can understand, concludes the Spanish sociologist, whose superficial analysis and ideological tendencies are truly disconcerting, "the growing accusations against Opus Dei of sectarian practices, and ultimately its being included among the list of cults that are harmful even for children, by experts of various tendencies" [61].

3. Some Conclusions

The scene I have briefly depicted allows us to draw, I think, some conclusions.

· The secularist anti-cult movement arose as having non-Catholic religious movements for its primary objective.

· The movement against Opus Dei started —especially within liberal Catholic circles— without any connection whatsoever with the polemic against "cults".

· In the first half of the 1980's, however, a part of the anti-cult movement extended its activity against its original enemies to cover other groups —Opus Dei among them.

· On the other hand, some Opus Dei adversaries within the Catholic ranks —typical examples of which are Fr Jacques Trouslard in France and Michael Walsh in England— realised that the anti-cult movement could offer them an ideological framework which suited their continued campaign, and provide them with powerful allies and greater resources. Initially, perhaps, the connection between the two movements arose from extrinsic and, at least partly, political reasons. But the anti-cult movement and the adversaries of Opus Dei within the Church did have in common a similar view of the world and of the role of religion which helped their mutual collaboration.

From all this one can make a further interesting and important observation. The secularist anti-cult position and the religious counter-cult position differ as to their objective reasons but do not necessarily present different subjective characteristics on the part of those who support such positions. Thus, for instance, if it is difficult to find militant atheists in the religious counter-cult movements, in the secular anti-cult movements one does find, on a personal level, people who declare themselves to be believers. I have on other occasions pointed out how, in the anti-cult movements of the United States, mainly directed by atheistic or agnostic "secular humanists", are found well-known figures of the different North American Hebrew communities. This fact was explained by Hebrew members of the anti-cult movement as a characteristic feature of Hebraism, which is not a missionary religion, and which is suspicious of any conversion attempt [62]. Alongside these representatives of the Jewish world some Protestants may be found —really very few— and finally a few Catholic priests and religious —occasionally also some lay people— who are few in number but very active.

One could well ask, why would a Catholic —and even more so if he is a priest or a religious— join in the activities of anti-cult movements, whose ideology, as soon as one gets to know or study it, is evidently hostile to religion in general, or at least hostile to the social relevance of religion, which should be especially dear to a Catholic. It is considered by some that the collaboration of certain Catholics with the anti-cult movement may be explained by their annoyance with "cults" which leads them to choose —wrongly, for they make the mistake of using a violent tone where a strong objective criticism would suffice— the hardest and most decisive line against new religious movements.

However, the history of the attacks against Opus Dei shows that such an explanation would only be valid for a very small number of Catholics whose naivety is as great as their lack of capacity to understand the complex reality of new religious movements and the anti-cult movement. But as for those Catholics who have opted for collaborating with the anti-cult movement, their choice shows a much more ominous way of thinking. They are, in fact, Catholics who know perfectly well the secularist ideology of the anti-cult movement but seek to make use of it as a weapon with which to attack, above all, their inter-ecclesial adversaries, by labelling them as "cults". It is certainly possible that some Catholics who today are actively involved in the anti-cult movement, may have discovered a late vocation to confront the new religious movements. But it is also true that, many years before they showed any concern for Jehovah's Witnesses or for Hare Krishna, some of them were already actively engaged in attacking Opus Dei. How can one therefore avoid thinking that the reason why "liberal" Catholics have joined the secularist anti-cult movement is not because they have recently discovered the "threat of the cults", but because they are eager to find powerful and wealthy allies, of similar ideologies, in their polemics against Opus Dei and other Catholic entities who wish to remain orthodox and faithful to the Magisterium? Even if one wanted to leave this question open, there are many signs that lead to an affirmative answer. What is more, we have abundant facts that justify the most serious reservations and the most well-founded doubts about the anti-cult movement and about the Catholics, who, with greater or lesser awareness, collaborate with the movement.

All this confirms the need for Roman Catholics to be interested in new religious movements, and even when necessary to enter into discussions about them. But this must be done from a Catholic point of view and according to specifically Catholic standards, which are very different to those of the secularist anti-cult movement, with which any form of collaboration by Catholics —as has become abundantly clear— is not only useless but indeed harmful and blameworthy.

[1] See Giulano Vigini, Colti, religiosi e saggi, in Avvenire, 23 March 1993, Gutenberg supplement.

[2] See Vittorio Messori, Opus Dei. Un'indagine, with a contribution written by Giuseppe Romano, Mondadori, Milan, 1994.

[3] See ibid., pp. 9-20 (p. 13).

[4] See ibid., pp. 21-48.

[5] See ibid., pp. 49-64.

[6] See ibid., pp. 65-83.

[7] See ibid., pp. 84-100.

[8] See ibid., pp. 101-113 (p. 103).

[9] Ibid., pp. 114-115.

[10] See ibid., pp. 114-121.

[11] See ibid., pp. 122-139 (p. 142).

[12] Ibid., p. 146.

[13] See ibid., pp. 140-148.

[14] See ibid., pp. 149-154.

[15] See ibid., pp. 155-169.

[16] See ibid., pp. 170-180.

[17] See ibid., pp. 181-196.

[18] See ibid., pp. 197-208.

[19] See ibid., pp. 209-236.

[20] See ibid., pp. 237-252.

[21] See ibid., pp. 253-281.

[22] See ibid., p. 251.

[23] Ibid., p. 252.

[24] Ibid., p. 239.

[25] See my Le nuove Religioni, SugarCo, Milan, 1989.

[26] See my article "Il movimento 'anti-sette' laico e il movimento 'contro le sette' religioso: strani compagni di viaggio o futuri nemici?", in Cristianità, year XXI, n. 217, May 1993, pp. 15-21. It was published in English with the title "Strange Bedfellows or Future Enemies?", in Update & Dialog, vol. I, n. 3, October 1993, pp. 13-22. There followed a series of letters written by members of the anti-cult movement answering in a tone that varied from the polemic to the offensive. Of particular interest was the letter written by Kevin Garvey, of the anti-cult organisation CAN, who instead of discussing the central theme of the article, only picked up the brief reference I made to Opus Dei. "We are not impressed, he comes to say, by his [Introvigne's] defensive remarks about Opus Dei. The growing ranks of former American members of Opus Dei presents incontrovertible proof that its practices violate every Catholic norm for personal spiritual development. Its moral theology breaches the boundary of Catholic heresy (...)". Kevin Garvey introduces himself as a "Roman Catholic", but says he is not interested as to whether the Pope thinks otherwise on Opus Dei. "I am not bound by the Pope's personal views about Opus Dei any more than I am by his proclivity for German phenomenology. Introvigne may not know this. But we do not know his relation to Opus Dei. We are curious, however, about his aderence to factual truths (...). We (...) would be most pleased if Massimo Introvigne [will make] a declarative statement about his association, or lack of association, with Opus Dei" (letter of Kevin Garvey to the editor of Update & Dialog, dated 8.4.1994). Leaving aside the tone of "conspiracy" of his last statement —whoever criticises the anti-cult movement must belong to the Opus Dei "cult"— it is surprising that a "Roman Catholic" should not know the difference between Pope John Paul II's proclivity for German Phenomenology (and perhaps even his being a fan of the Polish National football team), and the erection of Opus Dei as a personal Prelature or the Beatification of its founder.

[27] See William O'Connor, Opus Dei: An Open Book. A Reply to "The Secret World of Opus Dei", by Michael Walsh, Mercier Press, Dublin, 1991, pp. 66-69.

[28] V. Messori, op. cit, pp. 49-50.

[29] One of the most known "deprogrammers" still in action, Rick Ross, whose lack of expertise had such tragic consequences at Waco in 1993, had previously been involved in stealing jewels. See my article Che cosa é veramente accaduto a Waco, in Cristianità, year XXI, n. 217, cit., pp. 3-9.

[30] See Board Of Social And Ethical Responsibility. American Psychological Association, Memo to the DIMPAC committee, May 11, 1987.

[31] One of the many myths on this subject of the new religious movements is that they invariably maintain "right-wing" political opinions. Just to quote an example, which is far from irrelevant, the orange-robed followers of the late guru Osho Rajneesh were known for their association with "leftist" political forces in many countries of the world.

[32] See Giancarlo Rocca, L'Opus Dei. Appunti e documenti per una storia, Edizioni Paoline, Milan, 1985. We could well ask whether this old hostility towards Opus Dei found in certain Pauline sectors might not be linked with an exaggeratedly aggressive review of Vittorio Messori's book, signed by Renzo Giacomelli, Messori e l'Opus Dei: indagine o apologia? It appeared in Famiglia Cristiana, year LXIV, n. 11, 16.3.1994, p. 135. Its blatant ill-mannered tone represents an episode of journalistic bad taste that has few precedents, especially if one bears in mind that Vittorio Messori contributes regularly to Jesus, a magazine which is related to Famiglia Cristiana and published by the same editor.

[33] See Alberto Moncada, Historia oral del Opus Dei, Plaza & Janés, Barcelona, 1988. See V. Messori, op. cit, p. 55.

[34] See Penny Lernoux, Cry of the people, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1983.

[35] P. Lernoux, People of God. The Struggle for World Catholicism, Viking, New York, 1989, pp. 440-443.

[36] Interview of the author with Priscilla Coates, of the Cult Awareness Network, Santa Barbara and Buellton, California 1991.

[37] Statement by Basil cardinal Hume. Guidelines for Opus Dei in the Westminster Diocese, December 2, 1981, in Cultic Studies Journal, vol. 2, no. 2, Autumn-Winter 1985, pp. 284-285.

[38] On this point, see W. O'Connor, op.cit., p. 122.

[39] See Bernard Fillaire, Le Grand Décervelage, Plon, Paris, 1993, p. 180.

[40] Professional Profiles, in The Cult Observer, vol. 9, n. 5, 1992, p. 11. The Cult Observer is published by the United States anti-cult organisation, American Family Foundation.

[41] B. Fillaire, op. cit. pp. 189-190.

[42] Michael Walsh, The Secret World of Opus Dei, Grafton Books, London, 1989. A second, revised edition: Opus Dei. An Investigation into the Secret Society Struggling for Power within the Catholic Church, was published by Harper, San Francisco, 1992.

[43] Ibid., p. 199.

[44] For a detailed critique, chapter by chapter, see W. O'connor, op. cit.

[45] The author enjoys a regular cooperation with INFORM.

[46] B. Fillaire, op. cit., p. 190.

[47] P. Lernoux, People of God. The Struggle for World Catholicism, cit. p. 342 and p. 443, note 129.

[48] Ibid., p. 422. We are naturally not faced by a simple mistake in the quotations of Penny Lernoux and her informers. The most careful study of the publications and of the activities of Alleanza Cattolica during the whole course of its history could not have provided the least support for the accusations this American journalist claims, so that they can only be taken as mere delusions.

[49] See my book, Le sette cristiane. Dai testimoni di Geova al reverendo Moon, Mondadori, Milan, 1990. See Alberto Moncada, "Sectas católicas: el Opus Dei", a report presented to the Committee for the study of sociology of religion. Universidad Complutense, Madrid, July 1990, typewritten text, p. 1.

[50] Letter of Alberto Moncada to Massimo Introvigne, of 5.4.1991. The lower casing of "pontificate" and "pope" are of Alberto Moncada.

[51] Kenneth L. Woodward, A Questionable Saint. Is Opus Dei's Founder fit for Canonization?, in Newsweek, vol. CXIX, n. 2, 13.1.1992, pp. 52-53.

[52] See, for example, Paolo Passarini, Quel santo era un fan di Hitler, in La Stampa, 7.1.1992.

[53] See Joe Maxwell. Questions Persist about Opus Dei, in Christian Research Journal, vol. XVI, n. 3, Winter 1994, pp. 41-42. The Christian Research Journal, which is the main organ of the evangelical counter-cult movement in the United States, cautiously reports not only on the attacks of the secularist anti-cult movements but also on the replies given by Opus Dei.

[54] There were other Catholics, on the other hand, who decided to participate in any case. Such was the case of the anthropologist Alberto Lolli, representative of the Italian GRIS (Gruppo di Ricerca e di Informazione sulle Sette) who was a "relator" at the Barcelona congress.

[55] Alberto Moncada, Sectas católicas, el Opus Dei, paper read at the international congress on Totalitarian Groups and Cultism, Barcelona, 23/24.4.1993, typewritten, p. 5.

[56] Ibid., p. 7.

[57] Ibid., p. 14.

[58] Ibid., appendix, p. 2.

[59] See J. Maxwell, art. cit., p. 42, which reports on a virulent attack on Opus Dei by Ms Dianne Di Nicola one of the founders of the ODAN.

[60] Alberto Moncada, Sectas católicas, el Opus Dei, cit. p. 11.

[61] Ibid., appendix pp. 1-2.

[62] On this point, see my article: La questione della nuova religiosità, Cristianità, Piacenza, 1993.