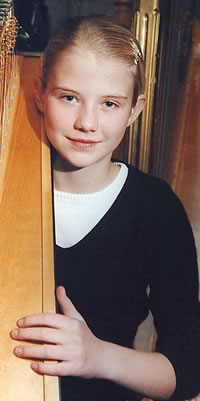

She didn't once call home, or contact friends, though she knew those closest to her feared the worst. She walked around freely, close to her own neighborhood, and apparently never made an effort to reach out for help. And when finally rescued, Utah teenager Elizabeth Smart did something that seems beyond comprehension: She denied her identity.

She didn't once call home, or contact friends, though she knew those closest to her feared the worst. She walked around freely, close to her own neighborhood, and apparently never made an effort to reach out for help. And when finally rescued, Utah teenager Elizabeth Smart did something that seems beyond comprehension: She denied her identity.

That a competent, thoughtful, normal teenager could act so compliantly in her own kidnapping has prompted speculation about cult-like programming and mind control. Although no one knows how her captor, self-styled prophet Brian David Mitchell, treated the teenager, there seems only one explanation. "She was brainwashed," her father, Edward Smart, told reporters.

Yet experts on the psychology of persuasion and abuse say notions of mind control are not necessary to explain the girl's behavior. Some of the possible motives are straightforward, others are bound with the unique pressures of adolescence and personality development.

"I think to call it all brainwashing is far too simplistic," said Richard Hecht, an expert on religion and psychology at UC Santa Barbara. "There are powerful motives for what appears to be very passive behavior, and they have to do with survival and the loss of any context and connection with the outside world."

The first and most obvious fact is the knife. Mitchell took Smart from her home at knife-point, in the middle of the night, according to the family. Darkness and threat would have been the foundation for any relationship that developed between captive and captor.

"She must have been simply terrified throughout the ordeal, living in constant fear that he could hurt her, and the best way to survive was simply not to act out," said Douglas Goldsmith, a child psychologist at the Children's Center, a Salt Lake City nonprofit clinic for emotionally troubled children. Yanked from a life of suburban affluence and forced to live as a vagabond, Smart would quickly have lost many of the things and people that reinforced her budding identity. From the evidence it appears she had very little say in even the smallest decisions while captive, such as what she wore and what she ate. Denied any autonomy, even a resilient human nature may begin to make compromises.

"Here she was camping out, in very different surroundings than she had known, living among the homeless, in caves, and clearly this is going to affect how you view yourself," said Cynthia Berg, a developmental psychologist at the University of Utah. By the time an escape opportunity came along -- Smart was seen several times in Salt Lake City, not far from her parents' neighborhood -- the captive may have turned her fear and disorientation into attachment to the adults who had control over her well-being.

Removal from the life she knew, along with the brutality of the kidnapping, could eventually have undermined her trust in that former world. A human nature so starved begins to identify with its tormentors.

The effect of Mitchell's religious pretensions cannot be ignored, however. Normally, converting someone to a belief system requires a dense network of fellow believers to teach values and rituals, as well as exert social pressure. Mitchell and his wife were only two people. Yet the forcefulness of their beliefs may have been enough to sway a girl of 14 years, just mature enough to comprehend spiritual ideas but not experienced enough to judge them skeptically, experts say.

From the standpoint of human social development, the teen years are a unique period when children are pushing away from their parents' influence and -- at the same time -- finding their place in the family's religious and cultural traditions. "Every study of religious conversion we have, going back to William James, tells us that adolescence is the time when the experience is most likely to happen," said H. Newton Malony, a professor of religious studies at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena.

Raised in a tradition with strong emphasis on respect for elders and authority figures, Smart may have had some predisposition to respect religious authority, however bizarre and intimidating Mitchell may have been, experts say. "Religious traditions leave deep imprints on people, even if they are not entirely aware of them, and during moments of extraordinary stress we may begin to apply those codes of behavior to survive," said Hecht. To label this stew of adaptation, self-protection and spiritual yearning as mind control distracts attention from the upsetting emotions that children recovering from kidnapping can feel, therapists say.

According to Linda Bortell, a child psychologist in South Pasadena, adolescents attempting to return to their normal life after an abduction are often mistrustful of adults and angry at people they thought should have protected them.

"These issues are going to persist, whether the kidnapping lasted nine days, or nine months," Bortell said. Assuming she was "brainwashed" allows the family to gloss over the emotions that must have tormented her, emotions that Elizabeth must come to terms with eventually, experts say.

"The question is how the family deals with them, and how resilient the child is," said Bortell.

BRAINWASHING AND MIND CONTROL CONTROVERSIES INDEX PAGE

[Home Page] [Cos'è il CESNUR] [Biblioteca del CESNUR] [Testi e documenti] [Libri] [Convegni]

![]()

[Home Page] [About CESNUR] [CESNUR Library] [Texts & Documents] [Book Reviews] [Conferences]